First Generation SPACs (1990s – Early 2000s)

The origins of SPACs (Special Purpose Acquisition Companies) trace back to the 1990s, following a crackdown on fraudulent blank check companies in the 1980s[1]. At the time, broker-dealers exploited unsophisticated investors through manipulative sales tactics in “boiler room” environments, promoting shell companies with the illusion of imminent acquisitions that would boost stock prices.[2] These schemes often left investors with worthless shares. Congress and the SEC responded to widespread fraud involving blank check companies by enacting the Penny Stock Reform Act of 1990 and implementing SEC Rule 419, which imposed strict regulations that effectively curtailed such offerings. As a result, the number of blank check companies plummeted from approximately 2,700 during 1987–1990 to fewer than 15 in the early 1990s[2].

In 1992, SPACs were introduced by a group of lawyers and underwriters as a safer alternative, incorporating investor protections absent in earlier vehicles.[3] However, by the mid-to-late 1990s, SPACs faded from relevance due to favorable IPO market conditions that allowed small companies to raise capital directly.

Second Generation SPACs (2003 – 2011)

The dot-com crash led to a decline in traditional IPO activity, creating an opportunity for SPACs to reemerge. In 2003, EarlyBirdCapital filed the S-1 for Millstream Acquisition Corp[4], marking the resurgence of SPAC activity. The appeal stemmed from the difficulty small companies faced in accessing public capital through conventional IPOs.

Despite their comeback, second-generation SPACs were plagued by hedge fund-driven greenmail tactics. Hedge funds exploited the requirement for over 80% shareholder approval for business combinations by threatening to vote against deals unless bought out at a premium.[5]

SPAC activity continued to rise despite a significant increase in the Federal Funds Rate between 2004 and 2006, suggesting that investor interest was driven more by arbitrage opportunities than interest rates[6]. In 2008, SPACs gained further legitimacy as NYSE and NASDAQ allowed them to list.[7] However, the global financial crisis curtailed this momentum.

A pivotal development came in 2010 when the SEC approved a NASDAQ rule allowing SPACs to use a tender offer structure in place of a shareholder vote[7]. This change enabled shareholders to “vote with their feet” by redeeming shares at trust value rather than blocking deals through formal votes.

Third Generation SPACs (2012 – 2016)

During this period, SPACs were viewed by IPO investors as low-risk vehicles with guaranteed capital return and embedded upside through warrants. SPAC units became structured like default-free convertible bonds: investors could vote in favor of a merger, redeem their shares for trust value, and retain warrants.[8]

While SPAC IPO investors enjoyed strong risk-adjusted returns[9], post-merger performance was generally poor[6]. A key moment in SPAC institutionalization came in 2012 when Justice Holdings, co-founded by Bill Ackman, merged with Burger King.[10] Though the deal didn’t trigger a SPAC boom, it signaled growing interest from major financial players.

Between 2012 and 2014, SPACs remained a niche product, making up only ~5% of IPOs and less than 2% of total IPO proceeds annually. Regulatory constraints, such as NYSE’s continued vote requirement, limited broader adoption. That changed in late 2016 when the SEC approved NYSE rule amendments to allow tender-only SPACs, setting the stage for explosive growth.

Fourth Generation SPACs (2017 – 2021)

By the end of 2016, all the ingredients for a SPAC boom were in place. Top investment banks like Goldman Sachs[11] and Morgan Stanley[12] began underwriting SPACs, and the NYSE permitted tender-only structures.

SPACs surged in popularity due to:

- Near-zero interest rates

- Massive fiscal stimulus

- Increased retail trading during pandemic lockdowns

Investors viewed SPACs as an appealing speculative tool with limited downside and high potential upside. The trust value was typically at or above 100%, and warrant structures sweetened the offering. Underwriters, too, became more incentivized by deferring fees or accepting compensation in equity and warrants. The participation of elite underwriters and exchanges elevated SPAC credibility. As demand surged, sponsors faced pressure to offer more investor-friendly terms, including fewer warrant, sponsor earnout and lock-up provisions, and reduced promote structures.

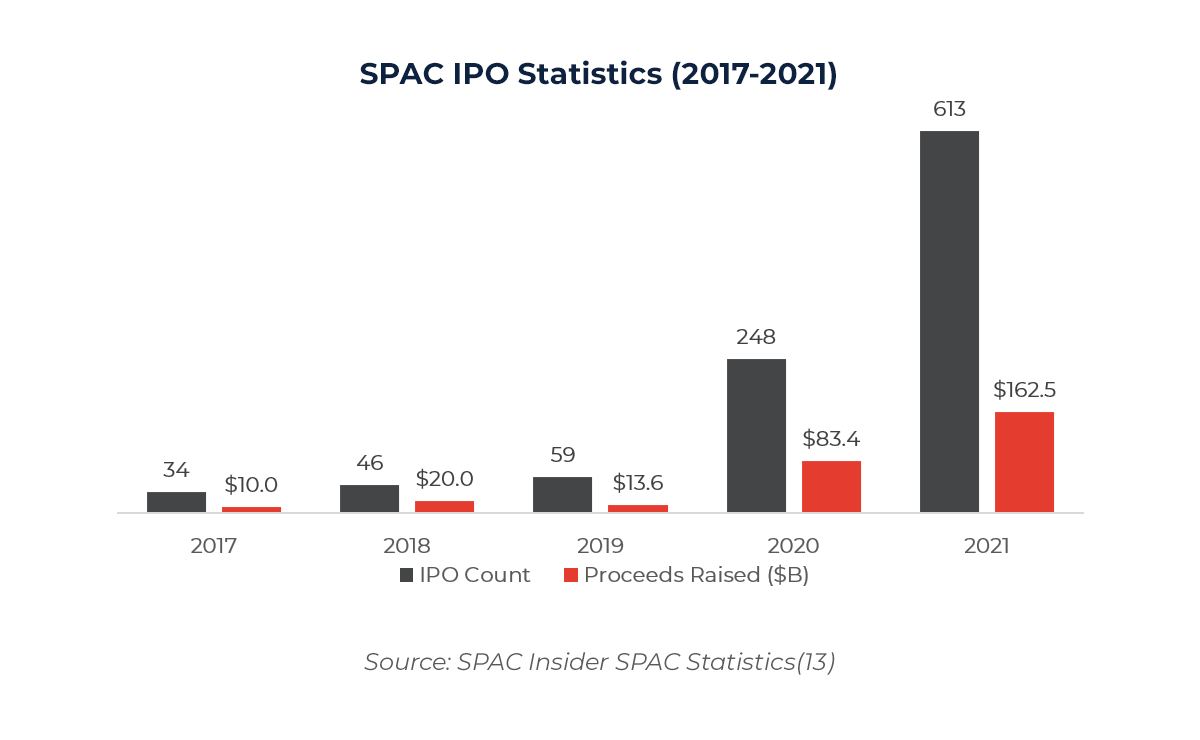

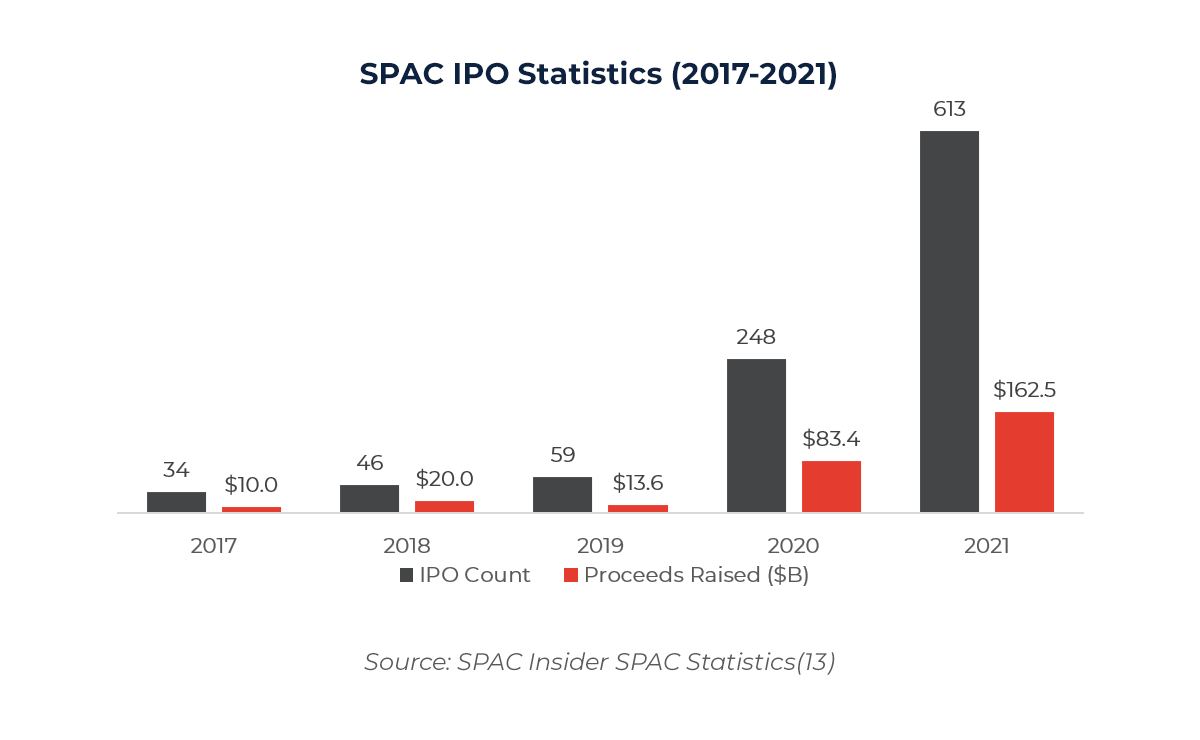

In 2020, SPAC offerings surged, with 248 IPOs raising over $83 billion. Then shockingly, in 2021 alone, 613 SPACs went public, raising over $160 billion and accounting for more than half of that year’s total IPO volume.[13] Toward the end of 2021, the SPAC boom slowed due to worsening market sentiment and growing fears of regulatory intervention.

Current Generation SPACs (2022 – 2024)

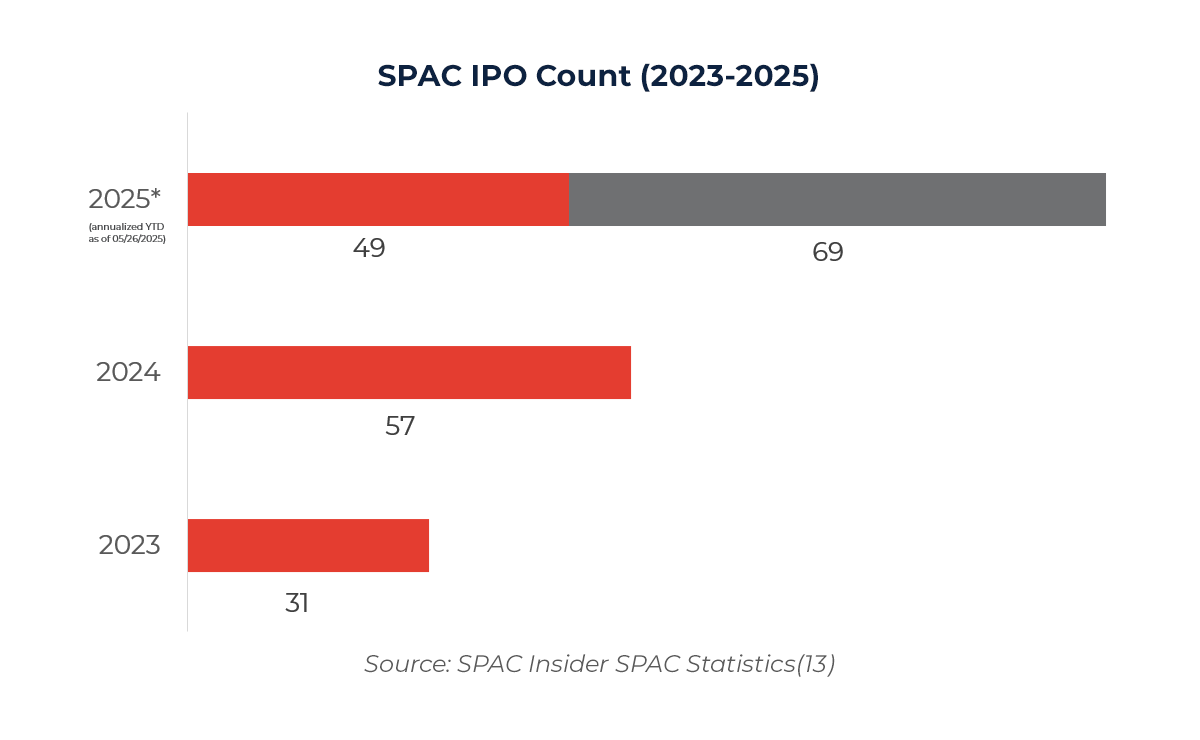

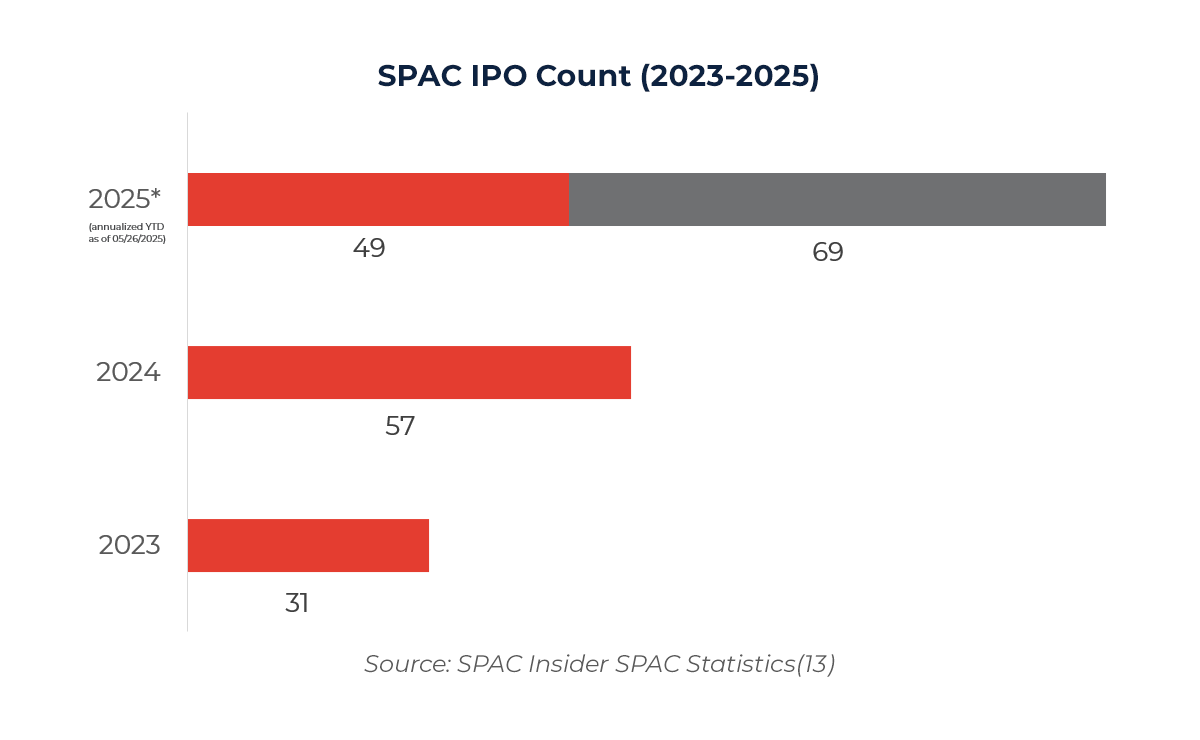

Between 2022 and 2024, SPACs have faced increasing criticism for poor post-merger performance and for shifting financial risk and costs onto retail investors. In response, the SEC under Chair Gary Gensler emphasized the principle of treating like cases alike, seeking to apply traditional IPO disclosure and liability standards to deSPAC transactions. On March 30, 2022, the SEC proposed new rules aimed at more tightly regulating SPACs, and on January 24, 2024, it adopted final rules designed to align deSPACs with traditional IPOs and create a more level regulatory playing field[14]. These regulatory changes significantly slowed SPAC formation during this period, with only 31 SPACs priced on U.S. exchanges in 2023, down from 86 in 2022.

Next Generation SPACs (2025 – Future)

In April 2025, Nasdaq introduced stricter IPO listing requirements to improve market stability and reduce volatility among small-cap listings. Companies that do not meet the Net Income Standard, defined as earning at least $750K in net income in two of the past three years, are now required to raise a minimum of $15M through their IPO to qualify for listing.[15] Nasdaq also revised how public float is calculated, excluding shares sold by existing shareholders from the minimum market value of publicly held shares.[16] These changes have made traditional IPOs more difficult for smaller, earlier-stage companies to pursue.

The regulatory reforms implemented between 2022 and 2024 laid the foundation for a healthier SPAC ecosystem, offering improved investor protections, enhanced issuer transparency, and clearer expectations for sponsors. Combined with Nasdaq’s tightened IPO requirements, these factors are creating a more favorable environment for SPACs to regain relevance and are catalyzing a renewed SPAC cycle in 2025.

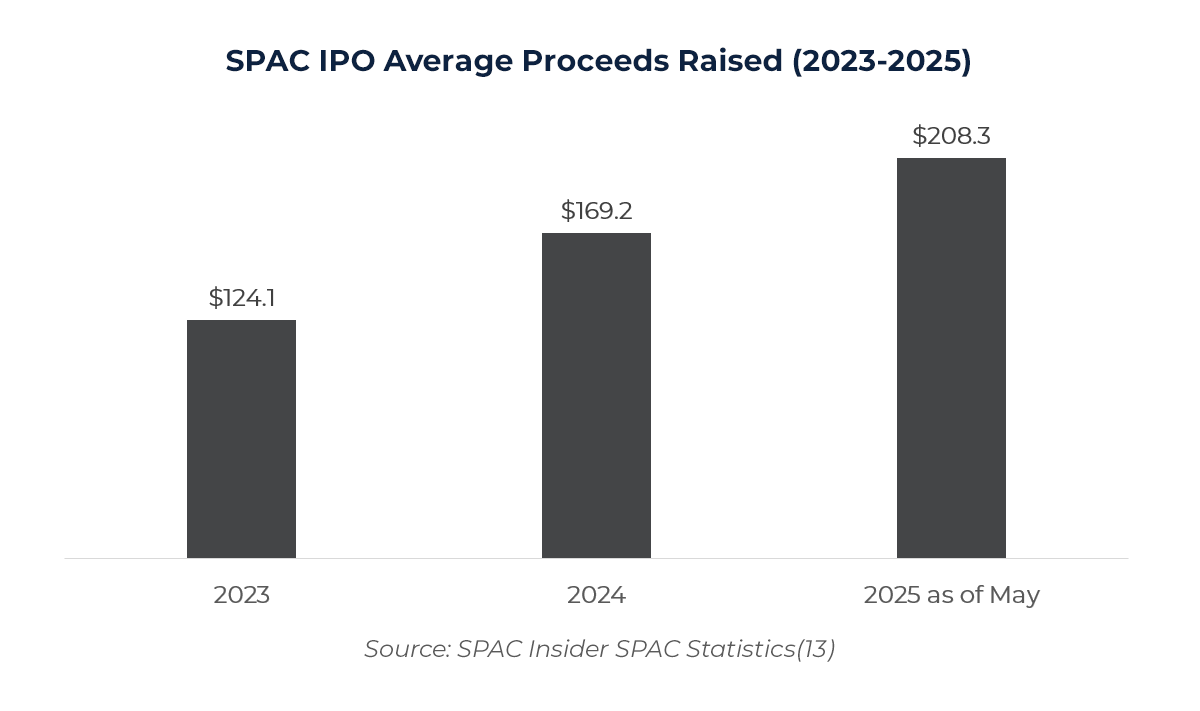

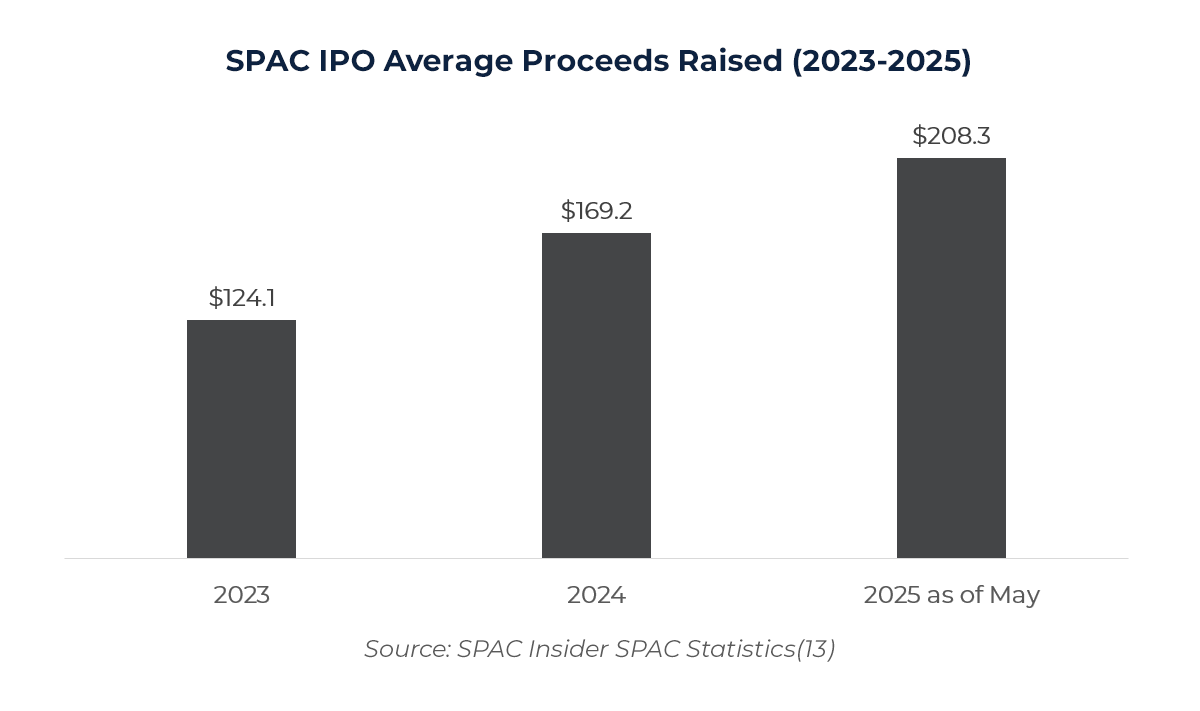

Although the total number of deals remains below previous highs, investor interest is clearly picking up. By May 2025, 49 SPAC IPOs have already been completed, nearly surpassing the full-year total of 57 in 2024. This uptick reflects a noticeable resurgence in momentum. At the same time, average gross proceeds per SPAC IPO have continued to rise, driven by a smaller number of high-quality, institutionally backed vehicles. The trend points to stronger PIPE and institutional investor participation, more efficient capital raising, and a lower cost of launching a SPAC.

In summary, SPACs have evolved significantly from their early reputation to become a more closely regulated and structurally disciplined financial vehicle. While activity slowed between 2022 and 2024 due to increased SEC scrutiny, these reforms have since created a stronger regulatory environment for all market participants. The introduction of stricter Nasdaq IPO listing requirements in 2025 has made traditional IPOs less accessible for high-growth, pre-profit companies, prompting many to turn to SPACs as more flexible alternatives. Sponsors are capitalizing on this shift by bringing forward higher-quality, growth-oriented targets. As a result, SPACs are regaining traction in 2025, supported by increasing deal size, stronger institutional backing, and favorable market tailwinds. With regulatory clarity and improving sentiment, SPACs are well-positioned for a potential new wave of growth.

References