After months of rising trade uncertainty, the US and Vietnam reached a deal to avoid harsher tariffs

After months of uncertainty sparked by President Donald Trump’s tariff announcement in April 2025, the US and Vietnam have reached a bilateral agreement. On July 2, 2025, Vietnam became the third country to finalize a new tariff accord with the US, following the UK and China. The deal comes just days before the original July 9 deadline, which has now been extended to August 1 via executive order.

The agreement introduces a more complex set of conditions for doing business across the US-Vietnam corridor. Its key elements include:

- A 20% US tariff now applies to a broad range of Vietnamese exports, ending the lower-duty access Vietnam previously enjoyed. This forces companies to reassess the long-term cost advantage of producing in Vietnam.

- A 40% tariff targets goods deemed to be “transshipped” through Vietnam, particularly those with significant Chinese content and minimal local value-add. The enforcement criteria, however, remain vague, leaving businesses in a compliance grey zone.

- In return, Vietnam will grant zero tariffs on US imports and provide preferential access for certain American goods.

- Looking ahead, the deal signals a turning point in how Vietnam positions itself in global trade. The country must localize more production, diversify its markets, and balance closer economic ties with both the US and China.

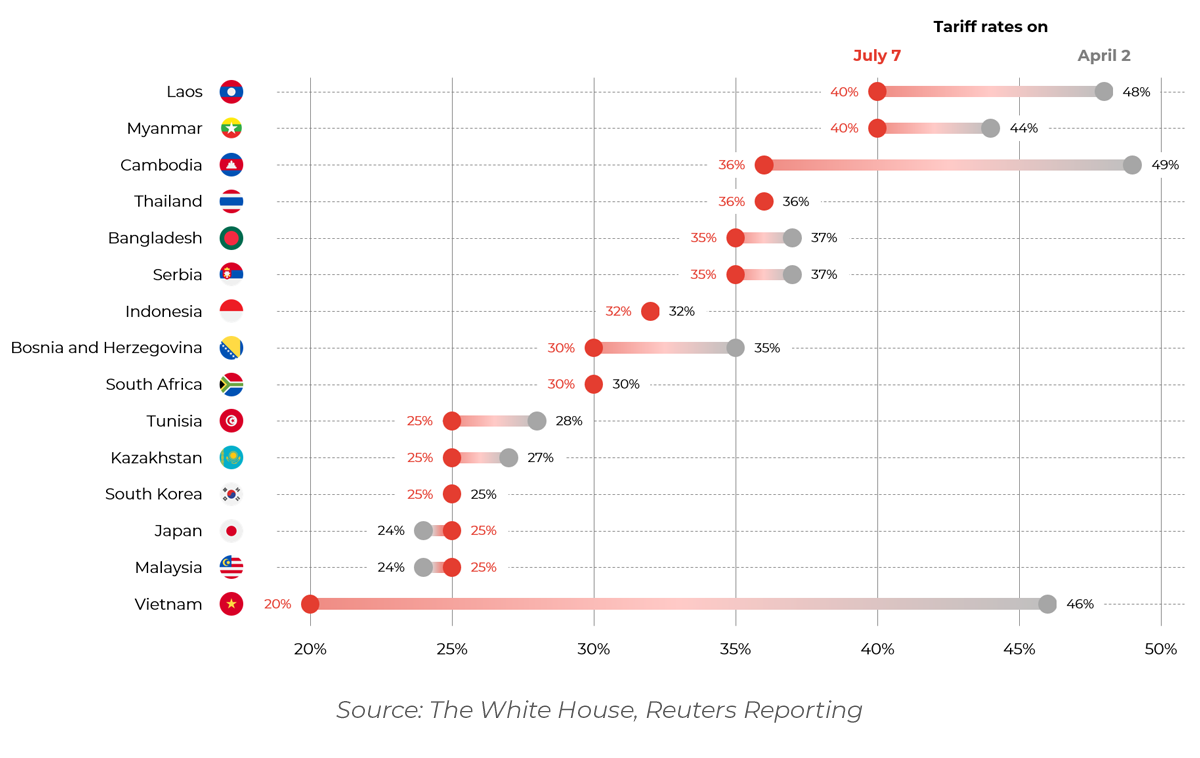

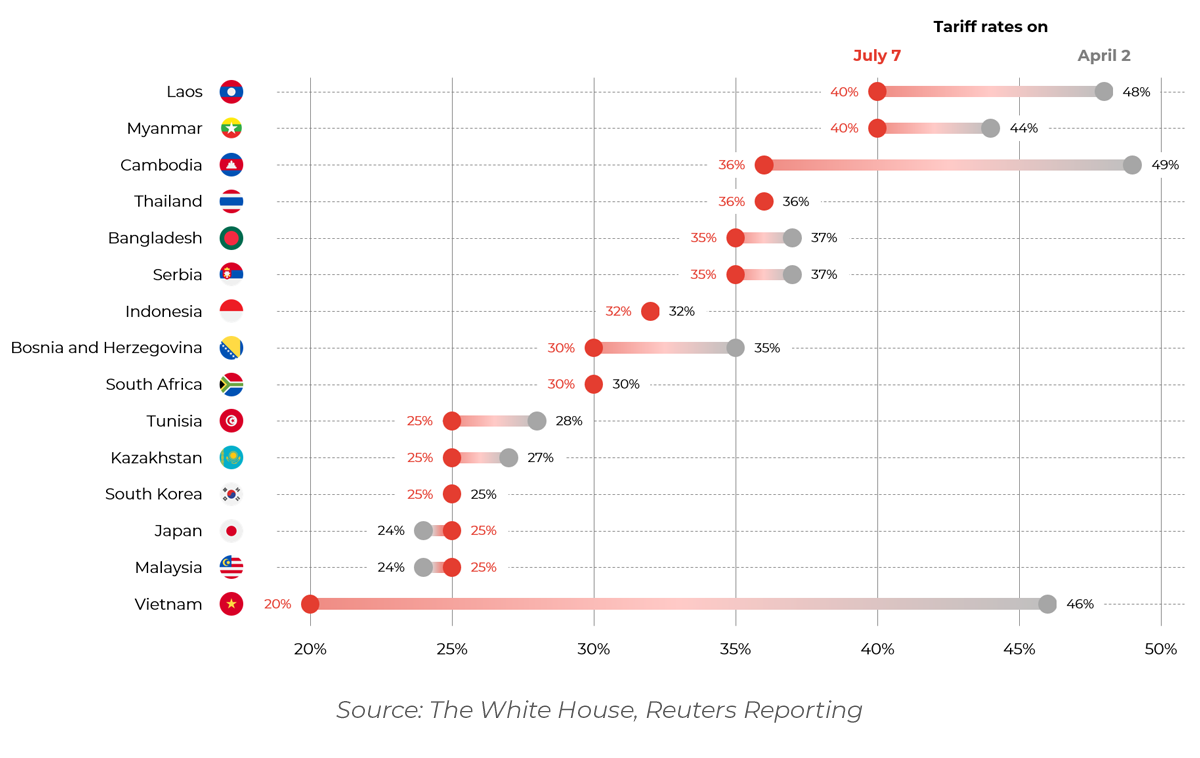

As of July 7, Vietnam’s current 20% baseline tariff stands at the lower end of reassigned rates, compared to 25% for Malaysia, South Korea, and Japan, and up to 40% for others like Myanmar and Laos. While this positions Vietnam relatively favorably, the extended enforcement deadline to August 1 leaves room for further negotiation and uncertainty.

Vietnamese exporters face a 20% US tariff, forcing companies to rethink China-to-Vietnam shifts

For businesses in Vietnam, the immediate impact is the new 20% US import tariff on Vietnamese goods, which fundamentally alters their cost calculus. Many Vietnamese exports that previously enjoyed low US duties (averaging just 2-10% under earlier agreements) now face a flat 20% tariff. This jump puts price-sensitive sectors at risk – textiles, footwear, furniture, seafood, and electronics, which are mainstays of Vietnam’s export model – will all become more expensive for US buyers. American importers estimate they could pay $28 billion more annually under these tariffs, and for products like footwear and apparel, retail prices might rise up to 10-20%. The result is a competitive squeeze on Vietnamese manufacturers: profit margins for exporters in low-cost, thin-margin sectors will shrink unless they can pass costs to consumers.

Crucially, the 20% tariff upends the strategy of companies that shifted production from China to Vietnam during the US-China trade tension. Firms that relocated to Vietnam to avoid US tariffs on Chinese goods are now seeing that advantage narrowed, as Washington imposes a 20% duty on Vietnamese exports as well. For businesses that previously fled China’s 25% tariffs (introduced in 2018-2019), this development marks another costly pivot. Instead of benefiting from relatively low US tariffs, these companies must reassess their supply chains and may consider moving again to alternate hubs. However, the alternatives provide no guaranteed safe haven; executives worry the Vietnam deal could set a template for US trade policy toward other low-cost countries. In the short term, larger multinationals might weather the cost by spreading production across regions or accepting slightly higher costs, while smaller suppliers with less flexibility could struggle to survive. The overall message is that Vietnam’s edge as a tariff haven has eroded, forcing firms to either absorb higher costs, raise prices, or seek new strategies.

At the same time, Vietnam’s commitment to eliminate import tariffs on US goods creates a new dynamic at home. American exporters, from soybean farmers and meat producers to automakers, now enjoy duty-free entry into Vietnam. This one-sided concession strongly favors US producers and opens Vietnam’s 100-million-strong market to a flood of competitively priced American products. For Vietnamese businesses, this is a double-edged sword. Local industries will face stiffer competition, for example, Vietnamese poultry and livestock farmers must now compete with cheaper US meat imports, and any domestic auto assembly ventures face pressure as US cars enter tariff-free. Consumer goods from the US, from apples to electronics, will likewise compete more directly with local offerings. On the other hand, Vietnamese companies and consumers gain opportunities from cheaper US inputs and technology. Manufacturers can import American machinery, components, and raw materials at lower cost, potentially boosting productivity. Consumers may see greater variety and quality in everything from food to high-tech gadgets. In some cases, Vietnamese firms might even partner with US brands as distributors or assemblers, leveraging the zero-tariff access. Overall, the Vietnamese market opens wider to the US, promising lower prices and new partnerships even as it challenges domestic producers to step up efficiency and innovation.

A 40% transshipment penalty deters Chinese inputs but leaves compliance uncertain

A key element of the accord is the 40% tariff on goods deemed to be “transshipped” through Vietnam, targeting Chinese products that are rerouted or lightly processed in Vietnam to bypass US tariffs. This provision aims to shut down loopholes and ensure that goods labeled “Made in Vietnam” genuinely meet origin requirements. It sends a strong signal to companies: final assembly alone won’t suffice if most of the value still comes from China.

In theory, this pushes businesses to localize more value-added production within Vietnam or source inputs from non-China suppliers. Vietnam has already begun cracking down on “relabeling” of Chinese imports, slapping anti‐dumping duties on Chinese steel and considering tighter local content rules to encourage more genuine manufacturing activity.

In practice, however, the rule is mired in ambiguity. The agreement doesn’t specify a clear threshold for what qualifies as transshipment. There’s no official guidance on whether it’s based on percentage of Chinese inputs, value-added, or product transformation, leaving companies unsure how to structure compliance. This lack of clarity has stalled investment decisions, particularly in sectors like apparel and electronics where Chinese inputs dominate. Indeed, while some foreign manufacturers in Vietnam (e.g. Taiwan’s AUO and Qisda) are retooling operations to avoid Chinese-origin tags, most are waiting for clearer enforcement rules before taking major action. Others are strengthening documentation and traceability to prepare for potential audits.

Until the US and Vietnam clarify enforcement, businesses face a regulatory gray zone, where the cost of non-compliance could be severe, but the rules remain undefined. The 40% tariff acts as both a deterrent and a risk multiplier, especially for firms caught between legal ambiguity and practical supply chain constraints.

Looking ahead, Vietnam and companies are adjusting strategies under the new trade paradigm

With the deal now in effect, both the Vietnamese government and foreign investors are adjusting their strategies to manage rising trade friction. On the governmental level, the priority is clear: preserve export access while reducing exposure to future tariffs. Policymakers are likely to accelerate investment in upstream industries, such as components, materials, and supporting manufacturing, to help domestic firms and foreign investors meet origin standards.

Policymakers may explore introducing local content requirements to ensure goods qualify as Vietnamese. At the same time, it is actively working to rebalance trade with the US, including increased purchases of American goods, such as aircraft, LNG, and agricultural products, to maintain diplomatic goodwill and reduce trade tensions. In parallel, Vietnam is also leveraging its numerous FTAs with other regions to reduce dependence on the US market. While the US remains Vietnam’s largest export destination, accounting for about 30% of total exports in 2024, Vietnamese exporters are increasingly pivoting to Europe, ASEAN, and CPTPP markets to diversify their trade portfolio. Vietnam’s advantage may no longer hinge solely on cost savings, which have diminished over time, but rather on consistent export performance, supply chain maturity, and broad trade access.

For businesses, this new environment demands more flexible and risk-aware supply chain planning. Multinationals may increasingly diversify their production across Vietnam and other regional hubs, such as India, Indonesia, or Malaysia, to reduce overdependence on any single country. Companies already operating in Vietnam are enhancing compliance protocols, reviewing their bills of materials, and exploring deeper localization of inputs to avoid falling under the 40% transshipment penalty.

With the EU and several other key trading partners still in negotiation with Washington, many Western firms are holding off on major supply chain moves. But as the August 1 deadline approaches and new tariff norms take shape, companies with substantial US exposure will need to reassess their entire Asia-based production strategy, not just final assembly hubs, but also upstream sourcing dependencies.

While Vietnam’s 20% tariff imposes new costs, it remains the most favorable among the announced affected peers, reinforcing the country’s position as a competitive and relatively lower-risk export hub. The rate represents a negotiated compromise rather than a punitive measure, helping Vietnam retain its role in global supply chains. Still, the deal signals a clear shift: passive tariff arbitrage is no longer viable. Businesses must now compete through strategic agility, robust documentation, and genuine local value creation to stay ahead.

Author:

Linhchi Trinh

Analyst

References